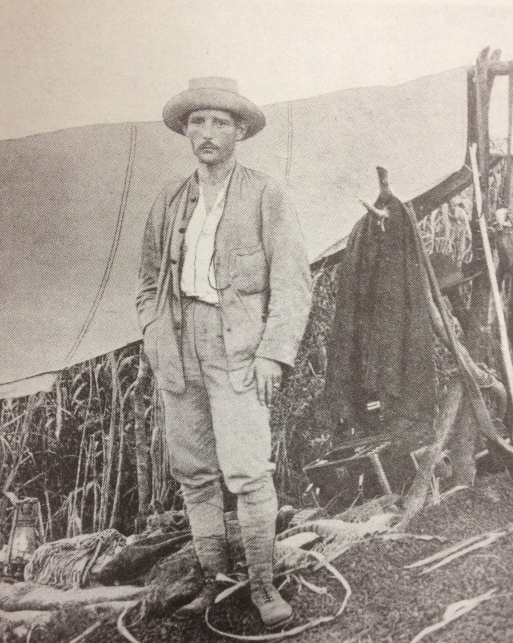

Robert de Wavrin de Villers au Tertre, more commonly referred to simply as the Marquis de Wavrin, was a Belgian aristocrat from Flanders who due to a family fortune derived from the ownership of coal-mines was able to dedicate his early adult life almost entirely to exploration and film-making in Latin America.

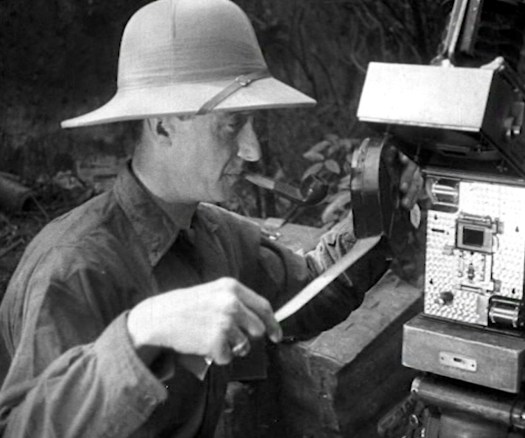

Although he had no formal training as an ethnologist, and thought of himself primarily as an adventurer and explorer, he became particularly interested in the indigenous peoples of South America and first took a Gaumont camera on his expeditions in order to document their way of life. Between 1924 and 1937, he released four major expedition films, all of which include passages of ethnographic interest: Au Centre de l’Amérique du Sud inconnue (1924), Au Pays du Scalp (1931), Chez les Indiens Sorciers (1934) and Vénézuéla, petite Venise (1937).

In addition, he produced a number of shorter, single subject films, but most of these are lost. One exception is a short film about a secondary burial ceremony as practised by the Yuko of the Sierra de Perijá on the Colombia-Venezuela border. As well as these films, de Wavrin also produced several books about his travels and took a large number of photographs.

The Second World War effectively brought de Wavrin’s travels in South America to an end. After the war, his participation in the world of South American ethnology and film-making became increasingly sporadic, and by the time that he died in 1971, both his writings and his films had fallen into obscurity.

It is only very recently that de Wavrin’s films have been recovered from this neglect, largely due to the remarkable work of Grace Winter, an archivist at the Royal Film Archive of Belgium. All of his films required a great deal of restoration, particularly the first, Au Centre de l’Amérique du Sud inconnue which had to be almost entirely reconstructed from dispersed fragments, some of them located in Paris.

This excellent work of restoration has been presented in a DVD collection released in 2017 by CINEMATEK, the publishing arm of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium. This contains all four major films, plus the Yuko ceremony film, as well as a number of other extras, including Marquis de Wavrin, Du manoir à la jungle, a biographical film about de Wavrin by Winter herself, produced in collaboration with the editor, Luc Plantier.

You must be logged in to post a comment.